The Santa Cruz River is a big reason why Tucson exists, and has for thousands of years. But, like other desert waterways, the river doesn't always flow. Reuse of treated wastewater is bringing sections of the riverbed to life.

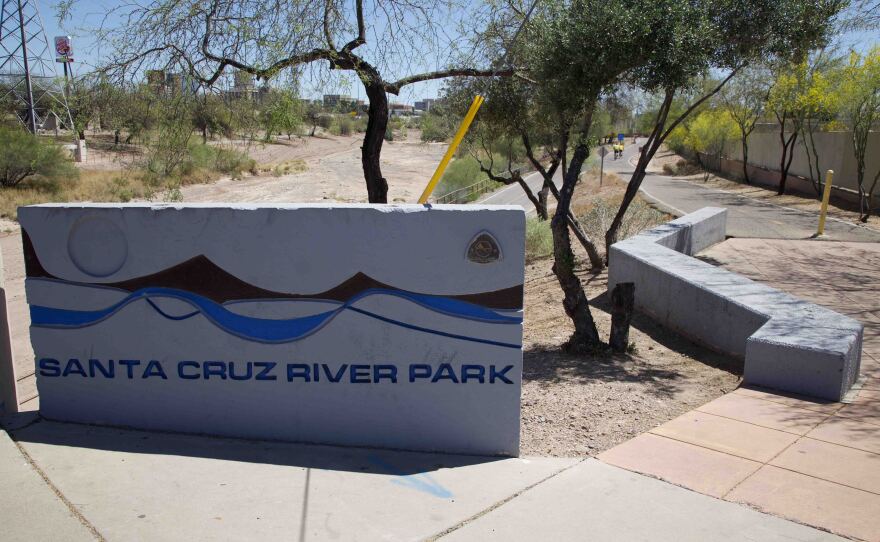

The paved path along the Santa Cruz is shared by moms pushing baby carriages, equestrians out for a morning ride, and cyclists exercising or commuting to work.

"Well, I usually use it from where the Rillito picks up at the Santa Cruz and ride all the way down through downtown. So it's really nice access to get to downtown through there. It's a really pretty section, it's really lush," Claudia Perchinelli said.

"We have 4,100 years confirmed years of agriculture here in the Tucson basin. It is the longest continually cultivated location in the United States because of the Santa Cruz River."

But in recent decades, the river wasn't always such an attractive gathering place.

Tucson would not be Tucson without the Santa Cruz River. The river that at times flowed nearly continuously has sustained humans and enabled agriculture in the U.S. and Mexico for thousands of years.

“We have 4,100 years confirmed years of agriculture here in the Tucson basin. It is the longest continually cultivated location in the United States because of the Santa Cruz River,” said Diana Hadley, a local historian who is active in restoring Tucson's birthplace along the Santa Cruz at the base of A Mountain.

Agricultural irrigation projects, development and groundwater pumping in this valley nestled between four mountain ranges depleted the Santa Cruz in the middle of the 20th century. The near-continual supply of water was gone by the 1940s.

The riverbed became the dumping ground for the city's treated wastewater. The quality of the discharge could barely sustain any life, and the effluent clogged the river bottom so water couldn’t soak into the ground to recharge the aquifer.

But the wastewater has proven to bring life back to the Santa Cruz. In the last few years, new wastewater treatment plants have improved the water quality and now provide perennial flows over about 10 miles. The river now supports fish, insects, birds, trees and vegetation from Tucson's west side north to Marana.

To the south, the Upper Santa Cruz River gets water from the international wastewater treatment plant on the Arizona side of the border.

The Santa Cruz is becoming a living river again.

"In the arid southwest, flowing rivers are a rare thing but they are the reason all of these communities are possible. And here in Tucson, the Santa Cruz River is the reason we can call Tucson home," said Claire Zugmeyer, an ecologist with the Sonoran Institute.

Zugmeyer has been shepherding the organization's Living River project for 10 years, tracking the river's health.

"We started seeing increased fish diversity and [were] really excited to see that the endangered Gila topminnow came back. That was a really big surprise."

"Before the upgrades on both stretches of the river we weren't really finding that many fish, and after the upgrades we started seeing increased fish diversity and really excited to see that the endangered Gila topminnow came back. That was a really big surprise and really fun to be out in the field and find that fish that we'd all been hoping for but didn't expect to find it so soon," Zugmeyer said.

The reclaimed wastewater is in great demand. The city water department uses it to irrigate parks, school playgrounds and golf courses and to recharge Pima County's most-visited bird-watching site, the Sweetwater Wetlands just south of one of the treatment facilities.

After the city takes what it needs, about 38 million gallons a day of the treated effluent goes into the river. After its release, the water flows north and slowly sinks into the riverbed, recharging the aquifer.

Timothy Thomure is the director of Tucson Water and said introducing water upstream of downtown will have many benefits.

"We are actively looking for ways to make that something that's a very long term aspect, and something that's not just a placeholder action with our water until we do something else with it. We're really looking at how do we get the most water management benefit out of that water while preserving or even restoring flow in the river," he said.

The infrastructure is in place to pipe the effluent back upstream for release near downtown, close to Tucson's birthplace. That could occur in 2019.

Caterpillar Inc. is constructing a new building nearby on the banks of the Santa Cruz for its surface mining and technology division that is now headquartered in Tucson. The company took that natural resource into account when planning the facility.

"Our new headquarters will be on the side of the river and is certainly part of the design as we look to blend with the natural landscape of the city and the environment around us," said Ben Cordani, the division's lead human resource manager.

Pima County is a partner in the Living River project. The county operates the two wastewater reclamation plants that provide the supply of water to the Santa Cruz.

“We’re putting this water back to beneficial use. It’s our water. We want to keep it within our community because we live in a desert. We want to ensure sure every drop of water we pump out of the ground, we put it to maximum beneficial use,” said Jeff Prevatt, the wastewater treatment department's deputy director.

"It's our water. We want to keep it within our community because we live in a desert. We want to ensure sure every drop of water we pump out of the ground, we put it to maximum beneficial use."

The Living River Project was honored in February by the National Association of Clean Water Agencies for its public information and education efforts through its annual reports.

The Santa Cruz river channel, like most other dry rivers throughout greater Tucson, draws bird watchers and walkers, cyclists and equestrians along The Loop, a pathway system built along 131 miles of water ways, including the Santa Cruz, throughout Pima County. Loop users celebrated the completion of the system in March.

"You don't even know you are in Arizona. I always take people who are visiting from out of town through that section because there's water and all of a sudden you're like look and if you just stand there for a while you see all of these beautiful birds. It's gorgeous. We love that section," cyclist Claudia Perchinelli said.

This piece is reproduced with the permission of Arizona Public Media: https://news.azpm.org/lifeblood/ It is part of a three-part “Lifeblood of the Desert” series by the Arizona Science Desk: KAWC Colorado River Public Media, Arizona Public Media, and KJZZ.

Part two of the series can be found in the related content section below.

Part three can be found on the KJZZ website: http://kjzz.org/content/633316/lifeblood-desert-salt-river-project-teams-turn-asu-robots-maintain-canal-system